Global disaster: glacier in Antarctica cracks at a record speed of 130 km/h

Researchers have obtained evidence of the existence of the fastest moving crack in the ice sheet.

The climate crisis that has hit the planet has a particularly dangerous impact on the ice-covered continent. Scientists have been studying glacial melting in Antarctica for years to predict the rate of ice loss and the consequences of this event for the planet. This time, however, they found something surprising and frightening, IFLScience writes.

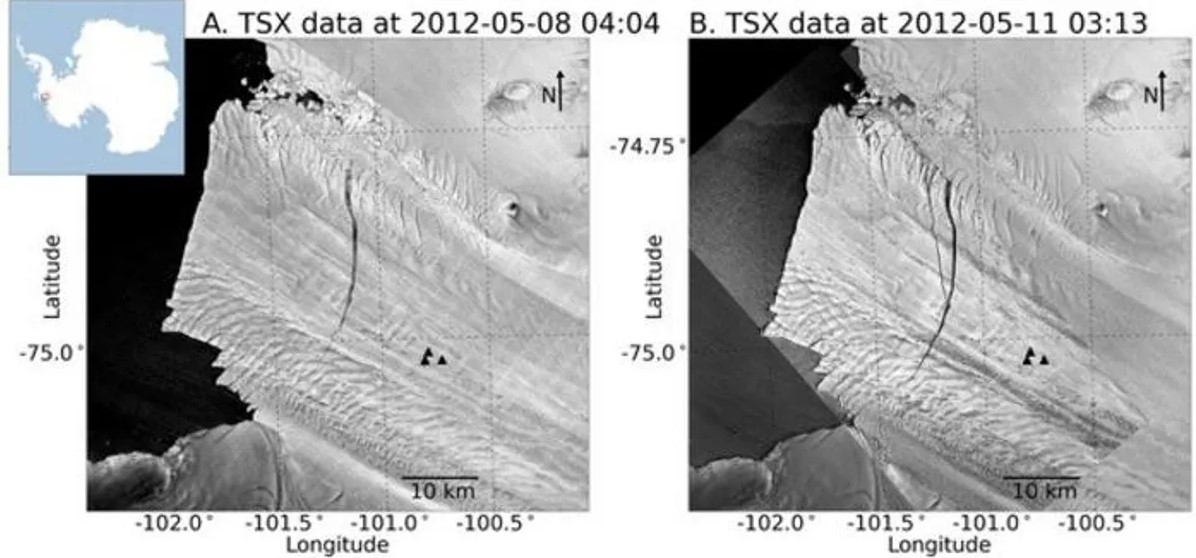

A team from the University of Washington observed the lightning-like appearance of a crack on the Pine Island Ice Shelf, which is the fastest melting Antarctic glacier, accounting for a quarter of the loss of all Antarctic ice.

Scientists conducted observations using data from instruments placed on the shelf glacier by other researchers, as well as radar observations from satellites. As a result, they obtained evidence of the fastest moving crack in the ice sheet ever recorded.

The data show that the 10.5 kilometer-long fault formed in the ice sheet at a speed of 35 meters per second, or 128.7 kilometers per hour. According to the study’s lead author, Stephanie Olinger, as far as scientists know, this is the fastest fault event ever observed by researchers.

It should be noted that the cracks that pass through the shelf glacier are called rifts. They are often the precursors to shelf calving, when large blocks of ice break off from a glacier and fall into the sea.

Photo: AGU Advances

Other faults in Antarctica tend to form over months or years, but a new study now shows that this can happen in a matter of seconds. Especially when it comes to the most vulnerable parts of Antarctica. According to Olinger, the new data suggests that with some evidence, the shelf glacier could split, and thus we should expect similar behavior in the future. The researchers also now believe that the large-scale ice sheet models used by scientists should be rewritten to account for these rapidly forming cracks.

Currently, scientists are focusing on understanding the physics of how glaciers break up, largely because climate change and further warming of the planet will inexorably lead to the melting of the Antarctic ice sheets, which in turn will only increase the frequency of fractures.

On short time scales, glacial ice behaves like a solid, but on longer time scales it is more of a “honey-like oozing liquid.” At the same time, new data provide evidence that glacial ice can actually break like glass. However, the team believes that the crack would have formed even faster if the ice had behaved as a brittle material.

According to Olinger, the new data give rise to the study of the physics of many different processes that affect the stability of Antarctic glaciers. By studying this issue, scientists are expected to be able to improve the efficiency of large-scale models and predict future sea level rise.