In the fall of 2021, the Mauritshuis Art Museum in The Hague opened an exhibition called “Scents in Color”. The curators placed fragrance dispensers next to the 17th-century paintings so that visitors could smell the images depicted on the canvas. The result was unexpected, if not unpleasant. The hints of cleanliness and fresh linen were overpowered by something we don’t often associate with upper-class life in the Dutch Republic, but which would be inevitable even for its wealthiest residents: the stench of Amsterdam’s canals.

Smell is an important but often forgotten aspect of history that is not easy to convey in writing or drawings. Thanks to science, researchers have been able to recreate historical odors, both unpleasant and fragrant, from the manure-covered streets of Europe’s busiest cities to the ashes of Roman funeral pyres. Interestingly, few scents from the past have proved as seductive as the perfume of Egyptian Queen Cleopatra VII, who was as infamous for her power as she was for her beauty.

The essence of Cleopatra

During the time of Cleopatra, Egypt had a long tradition of producing incense and perfume, which the country exported throughout the ancient world. The earliest known recipe for the flavor, known as kifi in Greece, dates back to the construction of the first pyramids. Whereas modern perfumes are alcohol-based, kiefi was made using animal fat and vegetable oil. They were burned together with resin, roots, and berries, creating smoke that the Egyptians used to flavor their homes and their clothes.

It is believed that the unique fragrance worn by Cleopatra came from Mendes, a prosperous settlement in the Nile Delta that played an integral role in the trade of spices from India, Africa and Arabia. Both the Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder and the Greek physician Dioscorides recognized Mendesian perfume as the best of its kind-the classic equivalent of Chanel No. 5, according to archaeologists who have tried to collect its long-lost recipe from various historical texts.

Since there are no surviving Egyptian sources that contain a complete recipe for Mendesian perfume, archaeologists had to turn to Greco-Roman sources to fill in the gaps. These reports agree on four main ingredients. In addition to resin and myrrh, the perfume also contained cassia, a less potent type of cinnamon plant, and balanos oil, a semi-drying oil produced from the seeds of Balanites aegyptiaca (Egyptian basalt), a tree native to North Africa and the Middle East.

Some sources recommend adding pure cinnamon to the mixture, while others do not mention cinnamon at all. The Byzantine physician Paul of Aegina provides one of the longest and most thorough lists of ingredients, which also includes terebinth, a cashew tree that was previously used as a source of turpentine. While the doctor prescribes only one pound of terebinth, other authors say the prescription calls for as little as ten. The same goes for balanos.

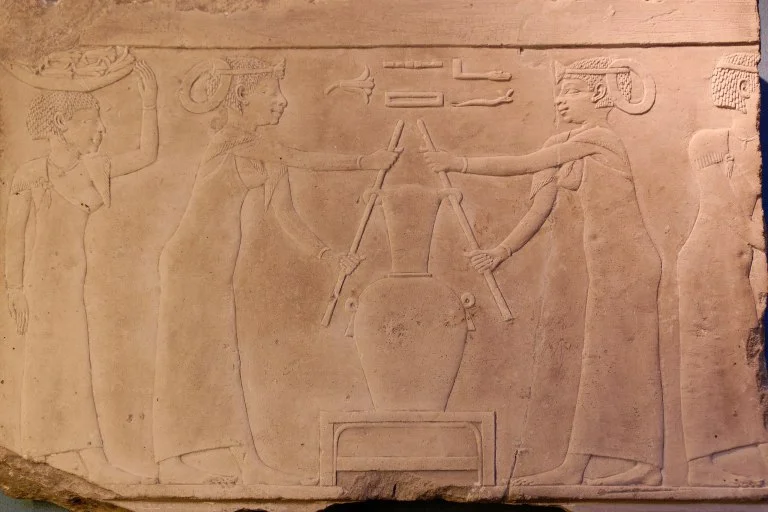

Sources differ not only on the ingredients but also on their preparation. The Greek philosopher Theophrastus, a student of Aristotle, said that the oil base of perfume should be boiled for ten days and nights before other ingredients can be added. Meanwhile, Pavlo says that perfumes should not be boiled, but rather kept on low heat for at least 60 days. He also says that the resin should be added last, and that the mixture should then be stirred for another week before storage.

In 2018, Egyptologist Dora Goldsmith and science historian Sean Coughlin recreated a possible version of Mendesian perfume by testing different combinations of ingredients, the most pleasant of which they described as “elegant” and “luxurious.” Described by the curator of olfactory art Caro Verbeek as “voluminous, red, strong, warm, rich, sweet and slightly bitter,” the spicy and subtle musky scent not only echoed the writings of Pliny and Paul, but also lasted longer than many other modern analogues.

Goldsmith and Coughlin’s experiment, while interesting, is by no means conclusive. As writer Elaine Valley discusses in an article written for Hyperallergic, it is impossible to know which Greco-Roman recipe corresponds to the original Egyptian one. The researchers’ second attempt, soon to be published, based on actual remains taken from a third-century BC perfume factory south of Méndez, promises to get closer to the actual recipe, as well as show how close they came the first time.

Cleopatra beauty treatment

For Cleopatra, perfume was just a small part of a much larger beauty routine. It is said that the Egyptian queen, who is credited with popularizing many unchanging cosmetic practices, used lipstick made from crushed carmine beetles, which continue to be used today to color everything from shampoo to lollipops. Cleopatra also bathed in milk – fermented donkey milk to be exact – to rejuvenate her skin, and may have washed her face with a mixture of honey, chalk, and apple cider vinegar.

Cleopatra’s beauty routine had an obvious economic component-in her time, the absence of stench was a luxury few could afford-but it also had a political component. According to both modern and ancient historians, the queen used her attractiveness as a tool for promotion and maintaining control over her kingdom. She did so when she established a romantic relationship with Julius Caesar and again when she rebelled against the Eternal City with the general and Caesar’s permanent successor, Marcus Antonius.

The Roman historian Plutarch mentions the perfume when he describes in detail her seduction of Antony. Sailing down the Kidnus River to meet her ill-fated lover, she is said to have rested on a canopy covered in gold, surrounded by servants dressed as cupids who fanned her perfume on the banks of the river. Contemporary historians have criticized this negative portrayal of Cleopatra as Augustus’ propaganda, viewing her not as a scheming siren but as an ordinary Egyptian woman who simply shared her culture’s love of perfume.