The Russian occupiers hunted down the last journalists in Mariupol, they managed to evacuate

Journalist Mstislav Chernov and photographer Yevgeny Maloletka, who shoot for the Associated Press, have been documenting events in the Ukrainian city of Mariupol for more than two weeks. They were the only international journalists who stayed in the city. Therefore, the Russian occupiers knew the names of the journalists and tracked them.

“We were reporting inside the hospital when militants started scouring the corridors. The surgeons gave us white coats to disguise ourselves,” the journalist says. After some time, a dozen Ukrainian soldiers broke into the hospital and took the journalists to the basement of one of the residential buildings.

Then the soldiers explained why they took them out of the hospital: “if you are caught, you will be filmed on camera and forced to say that everything you filmed is a lie.all your efforts and everything you did in Mariupol will be in vain.” The journalists were eventually evacuated to a safe place on March 15.

According to Chernov, he knew that Russian forces would consider the eastern port city of Mariupol as a strategic territory. Therefore, on the evening of February 23, he and his colleague Yevhen Maloletka, a Ukrainian photographer with the Associated Press, went to the city in a white Volkswagen van.

After the attack by Russian troops, the city was cut off from electricity and water almost immediately, food supplies began to run out, and eventually mobile phones, radio and television towers were cut off. Several other journalists left before the connection was lost and the city was completely blocked.

The lack of information during the blockade has two purposes. The first is that people do not understand what is happening and panic as a result. The second is the impunity of the occupiers. Without information from the city, without photos of destroyed buildings and dying people, Russian troops could have done whatever they wanted, if not for journalists and photographers, Chernov said.

Civilian casualties in the city began quickly, the journalist writes: “we watched as a doctor tried to save a little girl, but she died.”

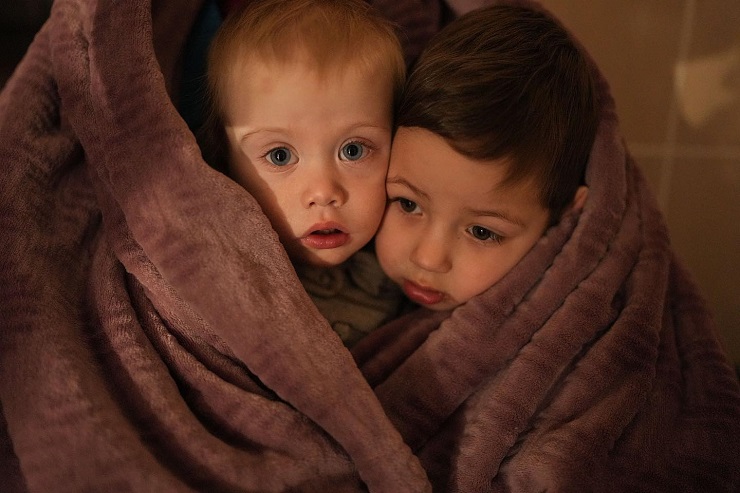

“The second child died, then the third. Ambulances stopped picking up the wounded because people couldn’t call for help, and doctors couldn’t move through the bombed-out streets. The doctors begged us to film the families who brought their dead and wounded, and allowed us to use their generator for cameras,” says the journalist.

At that time, there was one more place in Mariupol where one could catch a connection: near the looted grocery store on Budivelnykiv Avenue. Every day, journalists went there, hiding under the stairs to publish photos and videos.

On March 3, the signal disappeared. For several days, the only connection to the outside world was via satellite phone. And the only place this phone worked was in the open air, next to the shell.

People asked journalists when the war would end. There were rumors every day that the Ukrainian army was going to break through the siege.

“At that time, I witnessed deaths in the hospital, corpses in the streets, dozens of bodies dumped in mass graves. I have seen so many deaths that I filmed almost without perceiving them,” – Chernov says.

On the ninth of March, two airstrikes tore the plastic tape on the windows of the journalists’ van.

“We watched smoke rise over the Maternity Hospital. When we arrived, rescuers were still pulling bloodied pregnant women out of the ruins. Our batteries were almost completely drained, and we didn’t have a connection to send images. Curfew is only a few minutes away. The police officer heard us talking about how to report the explosion at the hospital. He took us to a power source and an internet connection,” the journalist recalls.

It took several hours to send the photos. At that time, the shelling continued, but the officers who accompanied the journalists around the city “waited patiently.”

During their work, the Russian Embassy in London posted two tweets, calling the AP photos fake and saying that the pregnant woman was an actress. The Russian ambassador showed copies of photos at a meeting of the UN Security Council and repeated the lie about the attack on the Maternity Hospital.

Ukrainian Radio and television were no longer working in Mariupol. The only radio that could be picked up broadcast “perverse Russian lies that Ukrainians are besieging the city, shooting at homes, developing chemical weapons.” The propaganda was so strong that some people we talked to believed it, despite what they saw with their own eyes, Chernov recalls.

On March 11, the AP editor asked by phone if journalists could find women who survived the airstrike on the maternity hospital to prove their existence.

“We found them in a hospital on the front line, some with babies, others just giving birth. We also learned that one woman lost a child and then her life. We went up to the seventh floor to send the video. From there, I watched tank after tank drive up to the hospital complex, each marked with the letter Z, which became the Russian emblem of war. We were surrounded by dozens of doctors, hundreds of patients, and US. The Ukrainian soldiers guarding the hospital disappeared. An hour has passed. Then Ukrainian soldiers approached us. It didn’t feel like a rescue. There was a feeling that we were simply being moved from one danger to another. At that time, it was not safe anywhere in Mariupol,” the journalist writes.

The Ukrainian military put them and a family of three in a Hyundai car and sent them for evacuation. On that day, about 30 thousand people left Mariupol — “so much so that Russian soldiers did not have time to carefully examine cars with windows covered with pieces of plastic.”

“People were nervous. They were fighting, shouting at each other. Every minute there was a plane or an airstrike. The ground shook. We crossed 15 Russian roadblocks. As we passed them, my hopes that Mariupol would survive were fading. At sunset, they approached the city destroyed by the Ukrainians to receive an offensive from the Russians. A Red Cross convoy of about 20 vehicles has already been stranded there. We all turned off the road into the fields together… when we reached the sixteenth checkpoint, we heard voices. Ukrainian voices. I felt a great relief. The woman in the front seat of the car burst into tears. We went out. We were the last journalists in Mariupol. Now they are not there,” Chernov recalls.