Climate warming and the concomitant development of the region may awaken pathogens that are older than the human species.

Humanity may face a dangerous new pandemic due to zombie virus strains or Methuselah germs frozen in the Arctic permafrost, scientists warn. According to them, a new global emergency may be triggered not by some disease that is new to science, but by a pathogen from the distant past.

For this reason, scientists have begun planning the creation of an Arctic monitoring network that will detect early cases of diseases caused by ancient microorganisms. It will also provide quarantine and qualified medical care to infected people in an effort to contain a possible outbreak and prevent infected people from leaving the region.

“Currently, the analysis of pandemic threats is focused on diseases that might originate in the southern regions and then spread north. On the contrary, little attention has been paid to an outbreak that could occur in the far north and then spread to the south – and I think this is an oversight. There are viruses there that could infect people and cause a new outbreak.” – Jean-Michel Clavery, geneticist at the University of Aix-Marseille

This point of view was supported by virologist Marion Koopmans from the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam. She noted:

“We don’t know what viruses lie in permafrost, but I think there is a real risk that one of them could trigger an outbreak of, say, an ancient form of polio.”

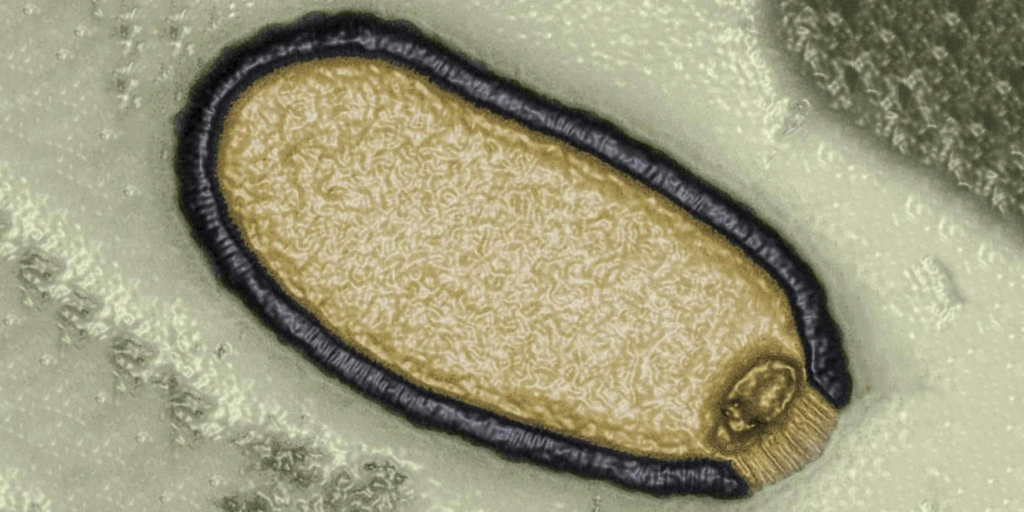

In 2014, Claveri led a team of scientists who isolated live viruses in Siberia and showed that they can still infect single-celled organisms, even though they have been dormant in permafrost for thousands of years. Further research, published last year, revealed the existence of several different strains from seven different locations in Siberia and showed that they could infect cultured cells. One of the virus samples was 48,500 years old.

“The most important thing about permafrost is that it is cold, dark, and oxygen-free, which is ideal for preserving biological material. You could put yogurt in permafrost and it would still be edible 50,000 years later.” – Jean-Michel Clavery

But permafrost is changing in the world. The upper layers of the planet’s main reserves – in Canada, Siberia and Alaska – are melting as climate change disproportionately affects the Arctic. According to meteorologists, the region is heating up several times faster than the average global warming rate.

However, the most immediate risk is not from melting permafrost, but from the disappearance of Arctic sea ice. This process makes it possible to develop shipping, transportation and industry in Siberia. Large-scale mining operations are planned there, during which huge wells will be drilled in deep permafrost to extract oil and ore. These operations will release a huge number of pathogens, Claveri added.

Koopmans emphasized the same point:

“If you look at the history of epidemic outbreaks, you will see that one of the key driving forces was changes in land use. The Nipah virus was spread by fruit bats that people drove out of their habitats. Similarly, monkeypox is linked to the spread of urbanization in Africa. And that’s what’s going to happen in the Arctic: a complete change in land use, and that can be very dangerous.”

Scientists believe that permafrost – at the deepest levels – may contain viruses up to a million years old. And they are therefore much older than our species, which appeared about 300,000 years ago.

Our immune system may never have come into contact with some of these microbes, and that’s another problem, Clavery added. The scenario of an unknown virus that once infected a Neanderthal returning to us, although unlikely, is now quite possible.